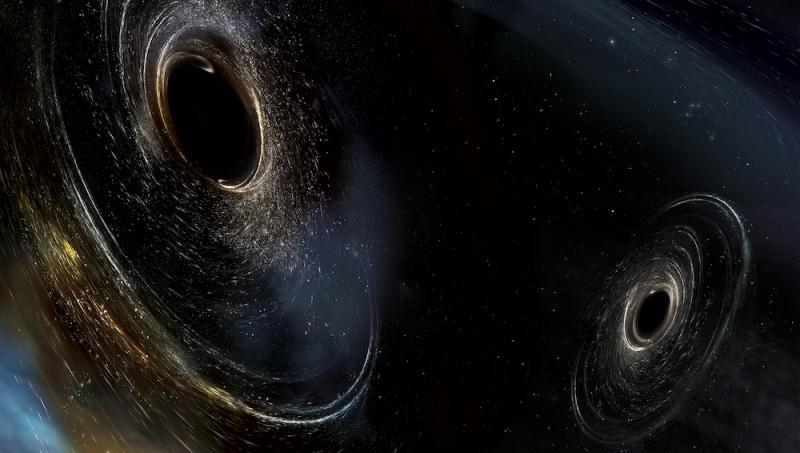

(Via LIGO and UIB) The LIGO Scientific Collaboration has made a third detection of gravitational waves. As was the case with the first two detections, the waves were generated when two black holes merged to form a larger black hole. LIGO is a group of more than 1200 researchers from more than 100 scientific institutions, spread over four different continents. From 2002, the Relativity and Gravitation Group from the Universitat de les Illes Balears forms part of LIGO. In addition, from June 2016 the Virgo Collaboration Group from the Universitat de València also participates in this association. Both groups have the support of the Spanish Supercomputing Network, which provides the computational resources needed to analyse data.

The third detection of gravitational waves (called GW170104) was made on January 4th 2017, in the current observing run of LIGO. Previously, this worldwide effort successfully led to the first-ever direct observation of gravitational waves in September 2015 during the first observing run of the LIGO detectors. Then, a second detection was made in December 2015. In all three cases, the detected gravitational waves were generated by extremely energetic collisions of black hole pairs.

The discovery, described in a new article in the journal Physical Review Letters, confirm the existence of an unexpected population of stellar-mass black holes that are larger than 20 solar masses. The new-found black hole, located about 3 billion light-years away (twice as far away than the two previously discovered systems), has a mass of about 49 times that of our Sun, an intermediate value between those previously detected in 2015 (62 and 21 solar masses for the first and second detection, respectively).

The newest observation also provides clues about the directions in which the black holes are spinning. As pairs of black holes spiral around each other, they also spin on their own axes. This is similar to a pair of ice skaters spinning individually while also circling around each other. Black holes can spin in any direction. Sometimes black holes spin in the same overall orbital direction as the pair is moving – what astronomers refer to as aligned spins – and sometimes they spin in the opposite direction. What’s more, black holes can also be tilted away from the orbital plane. The data analysis provides evidence that at least one of the black holes may have been non-aligned to the overall orbital motion, offering hints about how the pair formed.